Ways4eu WordPress.com Blog

SPA View of ways4eu.wordpress.com

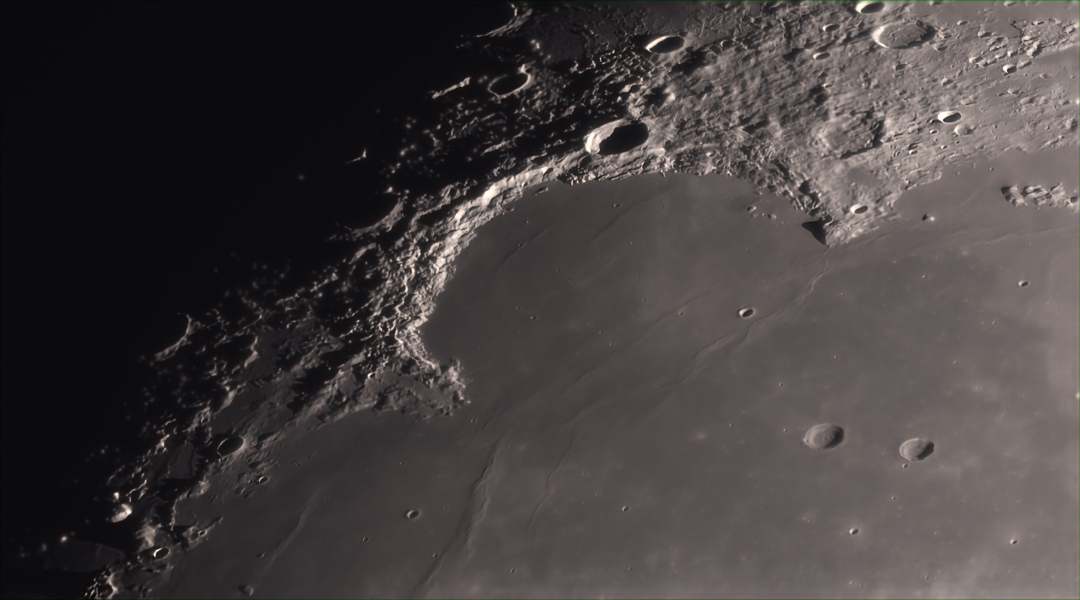

Sinus Iridum: The Moon’s Bay of Rainbows – A Poetic Lunar Journey

By JohnTheWordWhirlwind

on Fri Feb 13 2026

The Poetry of Lunar Cartography 🌙

On the Moon, maps come with poetry and Latin captions. The smooth, dark plains that greet the eye when you lift a telescope are called seas and oceans in the old, grand fashion—Mare Imbrium, Mare Serenitatis, and their many neighbors. It’s a naming convention that feels delightfully antique, a nod to Earth-bound cartographers who believed the Moon’s lunar plains were drowned oceans long before we learned otherwise. The twist, of course, is that these “seas” are dry, airless basins carved by ancient impacts and lava flows. If you squint just right, you can hear the Moon whisper, with a wink: “Welcome to Baroque geology, where the water’s just a memory.” 💫

Introducing Sinus Iridum: The Bay of Rainbows 🌈

Enter Sinus Iridum, the Bay of Rainbows. From a distance, this crescent of smooth basalt looks like a splash of iridescence across the Moon’s familiar face. It sits just beyond Mare Imbrium, a short hop from the Sea of Rains—the Mare Imbrium—where a telescope can reveal the gentle arc that frames the bay and hints at its turbulent birth. The Bay of Rainbows isn’t a literal rainbow; its Latin name Iridum evokes color and shimmer, a cosmic wink to the way sunlight plays across the basin’s rim.

The Lunar Landscape: Geography and Dimensions 🏔️

The bay stretches about 250 kilometers across, a generous bite of Moon-beholdable panorama. Its boundary is a ring of rugged, sunlit geometry—the Montes Jura, or the Jura Mountains—standing as a natural wall that keeps the bay’s mood from spilling into the neighboring basins. When local sunrise spills over the lunar topography, those mountains become part of the Sinus Iridum crater wall, turning the arc into a living line drawing across the sky. It’s as if the Moon took a pen to its own shoreline and traced an elegant smile, then forgot to wipe a fingerprint here and there. ✨

The Monumental Capes: Laplace and Heraclides

At the top of that sunlit arc sits Cape Laplace, a promontory that rises nearly 3,000 meters above the bay’s surface. It’s a cap that points toward the heavens and the memory of volcanic acceleration—the moment when the Moon’s crust cooled into a long, sculpted edge while the plains below held their quiet, basaltic breath. Down at the other end of the arc lies Cape Heraclides, which marks the bottom of the crescent and completes the boundary in the public imagination as much as in the lunar topography. 🗻

Giovanni Cassini’s Celestial Portrait 🎨

This specific boundary—Laplace at the crest, Heraclides at the opposite end—was immortalized by Giovanni Cassini in his 1679 lunar drawings. Cassini mapped the Moon as a moon maiden in profile, her silhouette curling in a timeless pose with long, flowing hair. The idea—Moon as a muse, a celestial portrait—fits the Bay of Rainbows as neatly as the curvature of its basalt floor fits the telescope’s field of view. If you tilt your head and peer through a historic instrument or a modern one, you can almost see Cassini’s artist’s touch in the way light and shadow sketch the bay’s edge.

The Poetry Meets Science 🔬

There’s a sly humor in these features: a lunar panorama named for rain while the Moon itself is a desert of dust and silence; a 250-kilometer arc that looks like a painted boundary between the old lava flows and the night sky; a topography that begs to be walked—if only by a future wave of explorers who will map not just the surface but the stories those surfaces tell. The Bay of Rainbows is more than a geographic location; it’s a reminder that science can measure height and distance while still letting imagination linger in the margins where Caesar’s maps meet Cassini’s moon maiden. 🌠

A Toast to Lunar Exploration ☕

So lift a metaphorical cup of tea to the Moon’s morning light: where seas are named for oceans of the past, valleys glow with geological history, and a crescent boundary between Laplace and Heraclides invites us to see science as a long, elegant portrait—one that’s still being drawn, one sunrise at a time. 🌅

Image via NASA https://ift.tt/384KThU